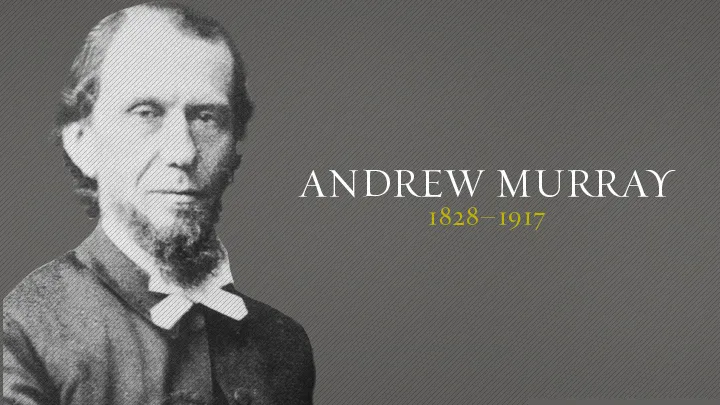

Jonathan Edwards was a prominent American theologian, philosopher, and revivalist preacher who played a pivotal role in the First Great Awakening.

- Research indicates he was born on October 5, 1703, in East Windsor, Connecticut, and died on March 22, 1758, in Princeton, New Jersey, at age 54 from complications related to a smallpox inoculation.

- As the only son in a family of 11 children, he grew up in a devout Puritan household, received a rigorous education at Yale, and became known for blending Reformed theology with Enlightenment ideas like those of Newton and Locke.

- Edwards served as a pastor in Northampton, Massachusetts, for over two decades, where he sparked and defended religious revivals, though he faced controversy over church practices leading to his dismissal in 1750.

- Later, he worked as a missionary to Native Americans in Stockbridge and briefly as president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), while producing influential philosophical and theological writings.

- His key works, such as sermons and treatises on free will, original sin, and religious affections, continue to shape Protestant thought, though his views on topics like slavery remain debated.

Early Life and Education

Jonathan Edwards grew up in a strict Puritan environment in colonial Connecticut. His father was a local pastor, and his mother came from a prominent clerical family, fostering an atmosphere of piety and intellectual rigor. He showed early promise, entering Yale College at just 13 years old and graduating in 1720. He pursued further studies in divinity, earning a master’s degree in 1723, and served as a tutor at Yale while developing interests in natural philosophy, optics, and theology. For more on his formative years, see resources like the Yale University archives or biographical works on early American education (e.g., https://www.yale.edu/).

Career and Ministry

Edwards began his ministerial career in 1727 as an assistant to his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard, in Northampton, Massachusetts, becoming sole pastor in 1729. He married Sarah Pierpont that same year, and they had 11 children. His tenure was marked by revivals during the Great Awakening, but tensions over communion standards—insisting on evidence of genuine faith—led to his ousting in 1750. He then served as a missionary in Stockbridge until 1757, before a short stint as Princeton’s president. Detailed accounts of his ministry can be found in historical analyses from sites like the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale.

Key Works

Edwards authored numerous sermons and treatises that defended Calvinist doctrines while engaging philosophical questions. Notable examples include:

- “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” (1741), a vivid sermon on divine judgment;

- “A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections” (1746), exploring true faith; and

- “Freedom of the Will” (1754), a seminal work on determinism and human choice. His posthumous publications, like

- “The Nature of True Virtue” (1765), further examined ethics and aesthetics..

American and Theologian Intellectual

Jonathan Edwards stands as one of the most influential figures in American intellectual and religious history, a theologian whose life bridged the Puritan legacy with Enlightenment rationality. Born on October 5, 1703, in East Windsor, Connecticut—a rural outpost in British America—Edwards was the only son among 11 children in a family deeply embedded in Congregationalist ministry.

His father, Timothy Edwards, served as pastor of the local church and supplemented his income by tutoring young boys for college, instilling in Jonathan a disciplined work ethic and love for learning. His mother, Esther Stoddard Edwards, daughter of the renowned Northampton pastor Solomon Stoddard, brought intellectual sharpness and independence to the household, creating an environment of Puritan devotion, family affection, and rigorous education. From a young age, Edwards exhibited precocious curiosity, writing essays on natural phenomena like flying spiders and engaging with advanced ideas in science and philosophy.

Edwards’s formal education began at home under his father’s guidance before he entered Yale College in New Haven at the remarkably young age of 13 in 1716. There, he immersed himself in the curriculum, graduating as valedictorian in 1720. He remained at Yale for two more years studying divinity, influenced profoundly by John Locke’s empiricism and Isaac Newton’s scientific principles, which he integrated into his theological framework. After a brief pastorate in a small Presbyterian church in New York City from 1722 to 1723, he returned to Yale to earn his Master of Arts degree in 1723 and served as a senior tutor from 1724 to 1726.

Born Again

During this period, Edwards maintained detailed notebooks on topics ranging from “The Mind” and “Natural Science” to “The Scriptures,” reflecting his broad interests in metaphysics, atomic theory, and biblical exegesis. He also experienced a personal spiritual conversion around 1721, shifting from intellectual assent to a heartfelt “delightful conviction” of God’s sovereignty, which became central to his piety and writings.

Marriage

In 1727, Edwards married Sarah Pierpont, a deeply pious and practical woman from a prominent New England family—her father co-founded Yale, and her lineage traced back to Puritan leader Thomas Hooker. The couple had 11 children, and Sarah managed the household with efficiency, allowing Edwards to dedicate 13 hours a day to study and writing. That same year, he was ordained as assistant minister to his grandfather Solomon Stoddard at the influential Congregational church in Northampton, Massachusetts, one of the largest in the colonies. Upon Stoddard’s death in 1729, Edwards assumed full pastoral duties, preaching on themes like justification by faith and God’s absolute sovereignty. His early sermons, such as “God Glorified in the Work of Redemption” (1731), critiqued Arminian tendencies that emphasized human free will over divine grace, blaming New England’s moral decline on self-sufficiency.

The First Great Awakening

Edwards’s ministry reached its zenith during the First Great Awakening, a transatlantic revival movement in the 1730s and 1740s that emphasized personal conversion and emotional religious experience. In 1733–1735, a local revival erupted in Northampton, with Edwards reporting over 300 professions of faith among the town’s 1,100 residents, particularly youth.

He documented this in “A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God” (1737), which detailed conversion patterns and spread the revival’s influence across America and Europe. The broader Awakening intensified in 1740–1742, fueled by itinerant preachers like George Whitefield, whom Edwards hosted and collaborated with. Edwards’s most famous sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” delivered in Enfield, Connecticut, in 1741, used stark imagery of hellfire and divine wrath to evoke terror and repentance, though he balanced it with offers of mercy.

While supporting the revivals, Edwards cautioned against excesses like fanaticism and bodily manifestations, defending the movement in works such as “The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God” (1741) and “Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival of Religion in New England” (1742). His “A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections” (1746) provided criteria for discerning genuine faith, arguing that true religion resides in holy affections—supernatural inclinations toward God—rather than mere enthusiasm or intellectual assent.

Growing Opposition and the Halfway Covenant

Despite his successes, Edwards faced growing opposition in Northampton. By the late 1740s, congregational disputes arose over church discipline and admission to the Lord’s Supper. Edwards rejected his grandfather’s lenient “Halfway Covenant,” which allowed unconverted individuals to participate based on moral behavior and doctrinal knowledge, insisting instead on visible evidence of regenerating grace.

This stance, outlined in “An Humble Inquiry into the Rules of the Word of God Concerning the Qualifications Requisite to a Complete Standing and Full Communion in the Visible Christian Church” (1749), alienated many, leading to his dismissal by a narrow vote on June 22, 1750. He delivered a poignant “Farewell Sermon” and later rebutted critics in “Misrepresentations Corrected, and Truth Vindicated” (1752). Though personally defeated, his views eventually reformed Congregational practices in New England.

Exiled from Northampton, Edwards relocated in 1751 to the frontier town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he served as pastor to a small English congregation and missionary to the Housatonic Native Americans. Despite challenges like language barriers, frontier wars, illness, and local opposition from exploitative settlers, he advocated for the indigenous people and continued his scholarly output. This period produced his most profound philosophical treatises, engaging Enlightenment critiques of Calvinism. In “Freedom of the Will” (1754), he redefined the will as the strongest inclination, arguing that human choices are determined yet free, compatible with moral responsibility and God’s sovereignty. “The Great Christian Doctrine of Original Sin Defended” (1758) responded to liberal theologians by affirming humanity’s innate corruption through biblical and empirical evidence, proposing a divine “constitution” for imputing Adam’s guilt. He also planned ambitious projects, including “A History of the Work of Redemption” (based on 1739 sermons, published posthumously in 1774), envisioning theology as a narrative of God’s redemptive plan across history.

Princeton University

In late 1757, following the death of his son-in-law Aaron Burr Sr., Edwards was elected president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). He assumed the role in January 1758, focusing on theological education and assigning essays on free will to seniors. Tragically, an experimental smallpox inoculation, intended to set an example amid an outbreak, led to his death on March 22, 1758, at age 54. His final words expressed trust in God’s will, and he was buried in Princeton Cemetery. His wife Sarah died later that year from dysentery while traveling.

New England Theology

Edwards’s legacy endures through his descendants— including U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr and numerous educators—and his intellectual contributions. He founded “New England Theology,” a school of thought that modified strict Calvinism toward greater emphasis on human agency, influencing 19th-century evangelicalism and missions. His ownership of enslaved individuals (at least seven documented, including Venus and Titus) complicates his reputation, as he defended limited forms of slavery while criticizing the Atlantic slave trade. Revived interest in the 20th century highlights his synthesis of faith and reason: an idealist metaphysics where the universe exists as ideas in God’s mind, ethics rooted in disinterested benevolence to “Being in general,” and aesthetics viewing beauty as harmony reflecting divine holiness. His works inspired missionaries, philosophers, and theologians, with modern editions available through the Yale University Press series.

| Major Work | Year Published | Brief Description |

| God Glorified in the Work of Redemption | 1731 (sermon) | Emphasizes human dependence on God for salvation, critiquing self-sufficiency. |

| A Divine and Supernatural Light | 1734 (sermon) | Describes saving knowledge as a supernatural sense imparted by the Holy Spirit. |

| A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God | 1737 | Documents the 1734–35 Northampton revival, analyzing conversion experiences. |

| Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God | 1741 (sermon) | Iconic depiction of divine judgment and the precariousness of unrepentant sinners. |

| The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God | 1741 | Defends the authenticity of revivals against critics. |

| Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival of Religion in New England | 1742 | Advocates for emotional preaching while warning against excesses. |

| A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections | 1746 | Outlines signs of true faith through holy affections and love for God. |

| An Humble Attempt to Promote Explicit Agreement and Visible Union of God’s People | 1747 | Calls for concerted prayer to advance revivals and missions. |

| The Life and Diary of David Brainerd | 1749 (edited) | Memoir of a missionary, inspiring global Protestant missions. |

| An Humble Inquiry into the Rules of the Word of God | 1749 | Argues for strict communion qualifications based on genuine conversion. |

| Freedom of the Will | 1754 | Philosophical defense of determinism, redefining will as motivated inclination. |

| The Great Christian Doctrine of Original Sin Defended | 1758 | Upholds Calvinist views on innate human sinfulness against Enlightenment critics. |

| The End for Which God Created the World | 1765 (posthumous) | Explores God’s glory as the ultimate purpose of creation. |

| The Nature of True Virtue | 1765 (posthumous) | Defines virtue as benevolence to Being, centered on love for God. |

| A History of the Work of Redemption | 1774 (posthumous) | Narrative theology tracing God’s redemptive plan through history. |

Edwards’s ideas on metaphysics (e.g., idealism and occasionalism), ethics (virtue as supreme love to God), and aesthetics (beauty as consent and harmony) remain subjects of scholarly debate, blending Reformed orthodoxy with modern philosophy.

Key Citations:

- Jonathan Edwards (theologian) – Wikipedia

- Jonathan Edwards | Biography, Beliefs, Sermons, Great Awakening, & Facts | Britannica

- Jonathan Edwards – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Jonathan Edwards: A Life: George M. Marsden – Amazon.com

- Edwards, Jonathan (1703-1758) | History of Missiology – Boston University

- Top Ten Edwards Books

- 7 “Must Read” Books on Jonathan Edwards – Reformed Forum